recommended reading

Exploring Art Song Lyrics: Translation and Pronunciation of the Italian, German & French Repertoire by Cheri Montgomery

Phonetic Transcription for Lyric Diction, Expanded Version, Student Manual by Cheri Montgomery

IPA Handbook for Singers by Cheri Montgomery

General Reading

Diction for Singers: A Concise Reference for English, Italian, Latin, German, French and Spanish Pronunciation by Joan Wall

A Handbook of Diction for Singers: Italian, German, French by David Adams

Russian

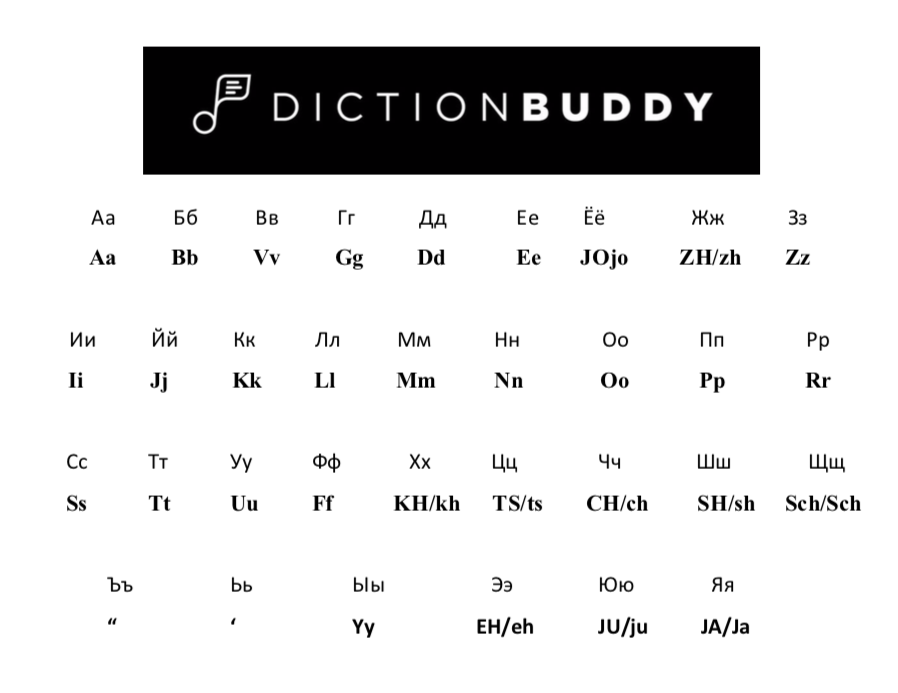

Below is the transliteration guide we utilize in creation of our Russian transliterations

Cheri Montgomery: Russian Lyric Diction Workbook

Check out this Wikipedia Page for More Information about Russian IPA and sounds:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Help:IPA/Russian

czech

Here are some concepts to be aware of when learning Czech Repertoire:

Useful website: http://www.locallingo.com

General Reading:

Singing in Czech: A Guide to Czech Lyric Diction and Vocal Repertoire by Timothy Cheek

french

The R in French Lyric Diction

French people don’t flip or roll the R’s. They use the uvular R, which is produced further back, between the tongue and the uvula, i.e., the tip of the soft palate. The uvular R is widely used in pop songs, chansons and cabaret repertoire. In opera, a long-time tradition has been to flip the R. It is widely recognized as an easier way to produce an operatic sound by allowing proper pharyngeal space. Although we acknowledge that both flipped and uvular R’s are present today on the international operatic stage, the latter being championed by some famous French opera singers, we have adopted the traditional approach to flip the R’s, which is a commonly accepted practice in North America.

The French schwa

The schwa, commonly referred to as “mute E”, is not pronounced in spoken French. However it is to be sung in classical repertoire. The normal pace reading generally features light unstressed schwas, while the slow pace delivers elongated schwas, close to the [œ] sound. The key to a correctly produced French schwa is to round the lips, while keeping the tongue in the [Ɛ] position.

Recommended Reading:

Singing in French: A Manual of French Diction and French Vocal Repertoire by Thomas Grubb

Advanced French Lyric Diction Workbook, Student Manual by Cheri Montgomery

French Lyric Diction Workbook Fourth Edition by Cheri Montgomery

german

The R in German lyric diction

Although flipped R is not used in spoken German, it is common practice to flip the R’s in classical singing, for the same reason they are flipped in French lyric diction. Post-vocalic R’s, i.e., placed after a vowel, are a thorny subject in German lyric diction. In spoken German they assimilate to a vowel sound similar to, but distinct from a schwa. In sung German, they can either be flipped or pronounced as a vocalic R. The tempo, the importance of the word and its position in the phrase are factors that will influence the decision of the singer. For standardisation purposes, the approach we have taken is to flip all the R’s. It is then up to the singer to make artistic choices.

The -ig suffix in German

When final, the -ig suffix is pronounced [Iç], i.e., the ich-Laut. Examples: heilig, selig.

When followed by a vowel, the g returns to it normal hard soung [g]. Examples: heiliger, Königin.

When followed by a consonant, it can be either pronounced with the fricative sound [ç] or the hard g [g]. It will depend on the word, the context, and denotes an aesthetic choice.

Examples:

Traurigkeit is pronounced with the ich-Laut

Ängstigt can be pronounced both ways. The fricative (i.e., the ich-laut) is more prevalent in the North, but the more formal pronunciation is plosive (i.e., with a hard g). Additionally, and especially because it is used in its reflexive form in Schumann’s “Die Lotosblume” (ängstigt sich), having two words in a row with a pronunciation of “ch” does not sound good. Therefore, DictionBuddy advocates to use a hard g, acknowledging that it’s a question of aesthetics.

A similar choice arises in French when it comes to liaison. In the song “Chanson triste” by Duparc, we would normally do the liaison between “baisers” and “et” in “tant de baisers et de tendresses”. But we would end up with two consecutive [z] sounds, which is not very elegant. It is therefore strongly suggested not to do this liaison.

Recommended Reading:

German Lyric Diction Workbook, Student Manual 5th Edition by Cheri Montgomery

German for Singers: A Textbook of Diction and Phonetics by William Odom and Benno Schollum

italian

Recommended Reading:

Italian Lyric Diction Workbook by Cheri Montgomery

Singers’ Italian: A Manual of Diction and Phonetics by Evelina Colorni

english

The R in English lyric diction

The burred R is not always opera friendly. Sometimes it is necessary to roll the R for the sound to carry and the text to be intelligible in a large hall. That’s especially the case for initial R’s. The pronunciation of the R’s is also governed by the choice of English dialect, for example American Standard (AS), British dialect, aka Received Pronunciation (RP), or a hybrid referred to as Mid-Atlantic (MA). Singing British repertoire and English oratorio involves lessening the R coloration of diphthongs and triphthongs, flipping intervocalic R, and rolling some R’s in initial position. Conversely, most of the modern and contemporary American repertoire will mainly use burred Rs.

Recommend Reading:

English Lyric Diction Workbook, 4th edition by Cheri Montgomery

The Singer's Manual of English Diction by Madeleine Marshall

Singing and Communicating in English by Kathryn Labouff

SPANISH

Recommended Reading:

A Singer's Manual of Spanish Lyric Diction by Nico Castel

POLISH

COMING SOON

LATIN

Recommended Reading:

Latin Lyric Diction Workbook by Cheri Montgomery